BLOG:A History of the World Cup in Ten Objects Part Three: The Vuvuzela and the music of the World C

In the last of three blogs, Professor of Sport Jean Williams looks at some of the artefacts that feature strongly in the history of the World Cup.

The Vuvuzela and the music of the World Cup

As the World Cup grew out of Olympic festival, which in itself celebrated artistic achievement as much as sporting endeavour, there have always been strong links with both high artistic culture, and popular forms of consumerism. Few England fans would be able to think of Italia ’90 without hearing the music of Luciano Pavarotti in their heads, since the extensive use of Nessun Dorma in the media coverage of the World Cup brought the Operatic aria to a wider audience. Pavarotti sang the song again to end his career at the 2006 Winter Olympics in Turin.

However, this was not an official World Cup anthem, which is often the case, since what is popular and what is official are often quite different. The official song for Italia 90 was the synthesiser-heavy Un’estate Italiana by Edoardo Bennato and Gianna Nannini. 1990 also produced one of the best popular songs for a World Cup, New Order’s World in Motion, which is probably the most worthy successor to 1970s Back Home. However, less than ten of the squad appeared in 1990 and John Barnes’ rap section is now famous, or infamous, depending upon how kitsch you like your popular culture. More classically, Placido Domingo had also sung the official World Cup song in 1982 named simply Mundial ’82. Also a classic was the Ennio Moricone Anthem, performed in 1978 by the Buenos Aires Municipal symphony. However, the political resonance of the tournament makes celebrating any aspect of its culture conflicting.

As we also know, there have been any number of truly appalling World Cup songs, written especially for the purpose. Lonnie Donigan’ s World Cup Willie song was an unofficial anthem, and somewhat nostalgic even by the standards of 1966. We’ve since been subjected to Dizzee Rascal and James Corden's rap reworking of Tears For Fears' hit Shout, and a version of the Baddiel and Skinner of Three Lions performed by Robbie Williams and Russell Brand. Official songs for the World Cup are now obligatory and this produces a lot of pressure for those chosen to perform. Since Los Ramblers promised to El Rock El Mundial in Chile 1962, there have been perhaps more misses than hits. Of course this depends on your personal taste, but Terry Venables singing If I can Dream World Cup song released in 2010, in conjunction with The Sun, was a personal low point for me, as an Elvis fan.

Collaborations for official songs often feature globally popular artists in recent times. The problems in 2014 Brazil were ignored with the unifying message: We Are One (Ole Ola) performed by Pitbull featuring Jennifer Lopez & Claudia Leitte. Germany 2006 had the Ricky Martin-esque Zeit Dass Sich Was Dreht sung by Herbert Grönemeyer featuring Amadou & Mariam. For South Korea/ Japan we had Boom by Anastacia, the relevance of which to football escaped most listeners. And so it goes on. Perhaps Ricky Martin’s 1998 La Copa De La Vida, The Cup of Life was one of the more upbeat performances at a World Cup.

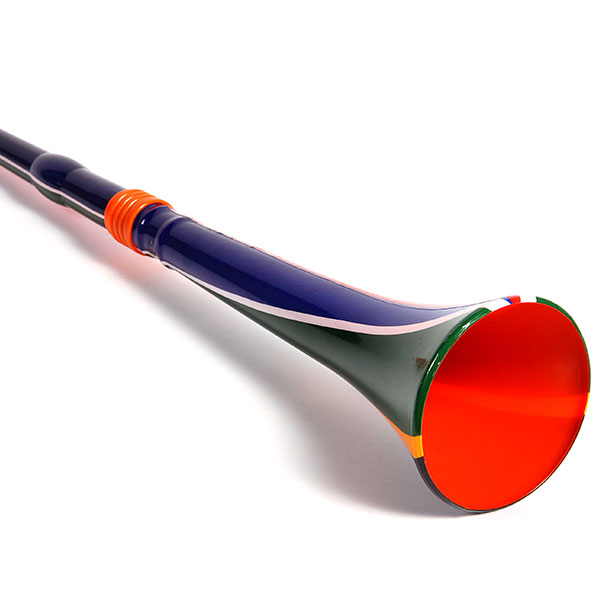

Vuvuzela

The official song for the South Africa World Cup was Waka Waka This Time For Africa, performed by Shakira and Freshlyground. Against this, the sound of the Vuvuzela changed the way a global audience heard the tournament, especially during matches.

Who invented the Vuvuzela? This is subject to much myth-making. Originally used to summon villagers to community gatherings, horns of this kind have several names, and different construction, which, it turn varies the monotone pitch produced. Fans of Johannesburg club Kaiser Chiefs claim a place in this history as do South Africa’s Nazareth Baptist Church. Whatever the case of how this traditional instrument became associated with football, it reached a global audience first through the 2009 Confederations Cup, as a curtain raiser for the World Cup itself in 2010. By this time, plastic manufacturers had produced them in their thousands and by the late 1990s and they had already became a standard feature of South African football.

Blown by a skilled individual the Vuvuzela is capable of a range of tones and pitches, but en masse the sound is less distinct and more muffled. There were complaints about the Vuvuzela in 2010 and even proposals to ban them. Players, visiting fans and TV executives, protested, bought ear plugs and raised health and safety concerns. Hyundai capitalised on the controversy by aiming to build the world’s largest working Vuvuzela as part of its marketing. But Sepp Blatter, FIFA’s-the President defended them, saying, ‘Africa has a different rhythm, a different sound.’

Banned from shopping centres, I much prefer the sound to the dreaded England band, who were not allowed to perform in 2014 due to a ban of musical instruments in the stadia. So the question of musical accompaniment to the World Cup looks set to remain controversial. Jason Derulo’s Colours is the official song of 2018, sponsored by Coca Cola. This corporate use of music is often contested by alternatives, and the Vuvuzela has an important place in history as an example of this.

- Jean Williams is Professor Sport and part of the University of Wolverhampton’s Institute of Sport and Human Science. She also works closely with the National Football Museum in Manchester.

For more information please contact the Corporate Communications Team.

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/Diane-Spencer-(Teaser-image).jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-18-19/220325-Engineers_teach_thumbail.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/241024-Dr-Christopher-Stone-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images/Maria-Serria-(teaser-image).jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/241014-Cyber4ME-Project-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240315-Research-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images/Kabaddi-WC-(teaser-image).jpg)